ABSTRACT

On Saturday 24th April 1993, a bombing incident took place at

approximately 10:25 a.m. within the Bishopsgate area of the city of

London. As a result, one person was killed and 34 people were injured.

Damage to building structures, fabric and contents, within a radius of

about 500 m of the device ranged from total devastation to minor damage.

As a consequence of this incident, the author was involved, as a

consultant to Griffiths Cleator and Associates (GCA), in the reinstatement

of over ten commercial buildings of various sizes, construction and

degrees of damage. Finite Element Analysis was carried out on two of these

buildings using ANSYS. A non-linear transient dynamic analysis was

performed on a 3-D model of a typical floor of the first building, and a

quasi-static analysis was performed on a full 3-D model of the second

building. This paper presents a brief overview of the bombing incident and

its damaging effects on building structures, outlines the investigation

and testing techniques used, discusses both types of FE analyses employed,

presents the dynamic response of the two buildings as predicted by FEA,

correlates the analysis results with the investigation and testing that

was carried out on site, and discusses the reliability of using FEA in

highlighting problematic zones in the structure. On Saturday 24th April 1993, a bombing incident took place at

approximately 10:25 a.m. within the Bishopsgate area of the city of

London. As a result, one person was killed and 34 people were injured.

Damage to building structures, fabric and contents, within a radius of

about 500 m of the device ranged from total devastation to minor damage.

As a consequence of this incident, the author was involved, as a

consultant to Griffiths Cleator and Associates (GCA), in the reinstatement

of over ten commercial buildings of various sizes, construction and

degrees of damage. Finite Element Analysis was carried out on two of these

buildings using ANSYS. A non-linear transient dynamic analysis was

performed on a 3-D model of a typical floor of the first building, and a

quasi-static analysis was performed on a full 3-D model of the second

building. This paper presents a brief overview of the bombing incident and

its damaging effects on building structures, outlines the investigation

and testing techniques used, discusses both types of FE analyses employed,

presents the dynamic response of the two buildings as predicted by FEA,

correlates the analysis results with the investigation and testing that

was carried out on site, and discusses the reliability of using FEA in

highlighting problematic zones in the structure.

INTRODUCTION

At approximately 10:25 on Saturday morning, 24th April 1993, a

terrorist bomb exploded in city of London. The device which was made of

unknown quantity of home-made explosives was carried in the back of a

vehicle that was parked on the Bishopsgate southbound carriageway in the

position shown in Fig.1. One person was killed and approximately 34 people

were injured. Building structures, fabric and contents, within

approximately 500 m radius of the device exhibited different degrees of

damage with the maximum being close to the bomb. At approximately 10:25 on Saturday morning, 24th April 1993, a

terrorist bomb exploded in city of London. The device which was made of

unknown quantity of home-made explosives was carried in the back of a

vehicle that was parked on the Bishopsgate southbound carriageway in the

position shown in Fig.1. One person was killed and approximately 34 people

were injured. Building structures, fabric and contents, within

approximately 500 m radius of the device exhibited different degrees of

damage with the maximum being close to the bomb.

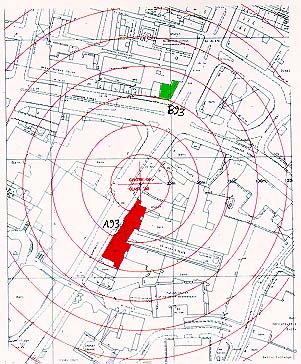

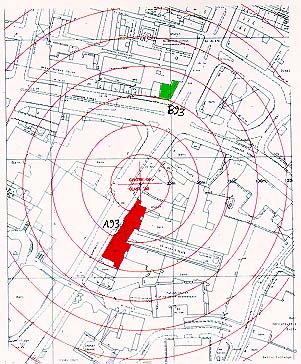

|

| FIGURE 1 |

| LOCATION PLAN OF THE SOURCE OF

DETONATION AND THE TWO BUILDINGS; BUILDING A93 MARKED IN RED;

BUILDING B93 MARKED IN GREEN. |

The 14th century St Ethelburga's Church, which was only about 7 m away

from the bomb, was practically levelled to the ground. The size of the

bomb was estimated to be approximately 850 kg TNT equivalent. This

estimation was based on specialist forensic evidence and study of the

crater measurements and the soil properties.

As a consultant to Griffiths Cleator and Associates (GCA) at the

time, the author was involved in the investigation and reinstatement of

over ten commercial multi-storey buildings with the closest being 11 m

from the bomb. As a consultant to Griffiths Cleator and Associates (GCA) at the

time, the author was involved in the investigation and reinstatement of

over ten commercial multi-storey buildings with the closest being 11 m

from the bomb. |

|

For the

purpose of this paper the number of buildings discussed shall be limited

to the ones modelled and analysed by FEA using ANSYS and they will be

referred to as A93 (marked in red in Fig.1) and B93 (marked in green in

Fig.1). The proximity of these two buildings to the source of detonation

is 11 m and 75 m respectively.

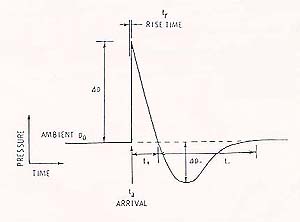

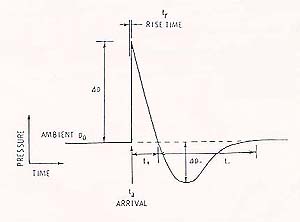

| FIGURE 2 |

| TYPICAL EXPLOSION WAVE PRESSURE

- TIME GRAPH. |

Royal Ordnance, being a division of British Aerospace Defence

Limited, was appointed to provide information on the magnitudes of the

blast pressures experienced by the two buildings, externally and

internally, in the form of time-history graphs at specific points of each

structure using 3-D simulation packages named 'INBLAST' and 'CHAMBER'.

This paper investigates the dynamic response of the two buildings as

observed on site on one hand and as predicted by FEA on the other hand. It

correlates the analysis results with the investigation and testing

findings, and discusses the reliability of FEA as a tool not only for

predicting the response but also in highlighting problematic zones that

may not be easy to observe on site without major opening up and breakage

of the structure. Royal Ordnance, being a division of British Aerospace Defence

Limited, was appointed to provide information on the magnitudes of the

blast pressures experienced by the two buildings, externally and

internally, in the form of time-history graphs at specific points of each

structure using 3-D simulation packages named 'INBLAST' and 'CHAMBER'.

This paper investigates the dynamic response of the two buildings as

observed on site on one hand and as predicted by FEA on the other hand. It

correlates the analysis results with the investigation and testing

findings, and discusses the reliability of FEA as a tool not only for

predicting the response but also in highlighting problematic zones that

may not be easy to observe on site without major opening up and breakage

of the structure.

|

2. CHARACTERISTICS OF BOMB

BLAST

An explosion is an instantaneous conversion of a small volume of

solid, or liquid, into a large and highly pressurised volume of very hot

gases that undergo violent expansion. As a result, a blast wave is

formed by the rapidly moving compressed air which is characterised by an

instantaneous rise in pressure. This is followed by a decay over a period

called the positive phase duration (see Fig.2). As the energy of

the expanding gases becomes dissipated, their momentum falls and they

begin to contract, creating a suction phase known as the negative

phase. At this phase, the blast wave pressure is below ambient

(atmospheric) pressure. An explosion is an instantaneous conversion of a small volume of

solid, or liquid, into a large and highly pressurised volume of very hot

gases that undergo violent expansion. As a result, a blast wave is

formed by the rapidly moving compressed air which is characterised by an

instantaneous rise in pressure. This is followed by a decay over a period

called the positive phase duration (see Fig.2). As the energy of

the expanding gases becomes dissipated, their momentum falls and they

begin to contract, creating a suction phase known as the negative

phase. At this phase, the blast wave pressure is below ambient

(atmospheric) pressure.

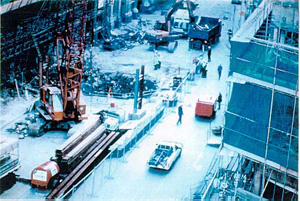

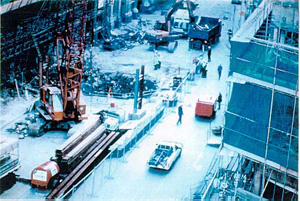

If the explosion is contained by soil at a considerable depth

from the ground surface, the energy will be converted into vibrations that

propagate through the ground as seismic waves. At lesser depths, as is the

case here, smaller proportions of the energy will be transmitted as

seismic waves and much of the explosive force will be absorbed by the

earth close to the surface displacing it and forming a crater (see

Plate-1). If the explosion is contained by soil at a considerable depth

from the ground surface, the energy will be converted into vibrations that

propagate through the ground as seismic waves. At lesser depths, as is the

case here, smaller proportions of the energy will be transmitted as

seismic waves and much of the explosive force will be absorbed by the

earth close to the surface displacing it and forming a crater (see

Plate-1).

| PLATE 1 |

| CRATER FORMED BY THE EXPLOSION

OF THE BOMB (DIAMETER = 9M; DEPTH =

2.5M). | |

|

As the blast waves radiate out within the confined city streets

they will be reflected and refracted by adjacent buildings. The blast

waves will travel over the tops of buildings and down light wells thus

totally enveloping these buildings and subjecting them to large unbalanced

transient blast loads such as pressure pulses, gas filling and linear

windage all of which have different times of arrivals. The geometry of the

individual buildings, and in particular their elevations, can further

magnify the incident transient blast loads. As the blast waves radiate out within the confined city streets

they will be reflected and refracted by adjacent buildings. The blast

waves will travel over the tops of buildings and down light wells thus

totally enveloping these buildings and subjecting them to large unbalanced

transient blast loads such as pressure pulses, gas filling and linear

windage all of which have different times of arrivals. The geometry of the

individual buildings, and in particular their elevations, can further

magnify the incident transient blast loads.

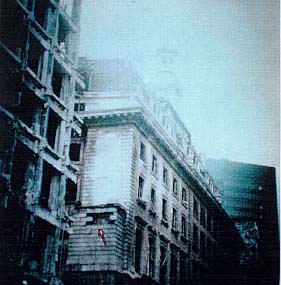

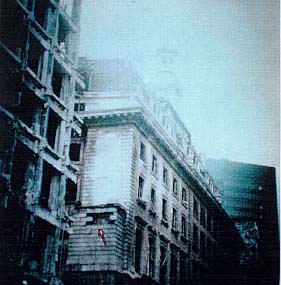

| PLATE 2 |

| BUILDING A 93. (NOTE THE

DAMAGE INDICATED BY THE RED ARROW). |

The blast loads, although being transient in nature, would

nevertheless have been many orders of magnitude greater than the original

structural design loads for the buildings within the affected zone. Due to

the random nature of blast loads, damage to building structures is

notoriously unpredictable. Depending on the location of the explosive

device, the configuration of the surroundings and the quantity of free

space into which the gas may expand, the effects of a given explosive

device on a structure are notoriously unpredictable. The blast loads, although being transient in nature, would

nevertheless have been many orders of magnitude greater than the original

structural design loads for the buildings within the affected zone. Due to

the random nature of blast loads, damage to building structures is

notoriously unpredictable. Depending on the location of the explosive

device, the configuration of the surroundings and the quantity of free

space into which the gas may expand, the effects of a given explosive

device on a structure are notoriously unpredictable.

|

3. DESCRIPTION OF THE TWO

BUILDINGS

3.1 Building

A93

This was a grade II listed steel framed building, 7 storey high

constructed in 1928 (see Plate-2). Its architectural form can be described

as stone classical facade. Above 5th floor, the elevation steps inwards

and extends up the 7th floor where it was crowned with a cornice. Above

this was a steep slated mansard roof with dormer windows. The structural

frame was made up of plated mild steel R.S.J's (Beams and columns) or made

up plated beams secured with rivets and either riveted or bolted end

connections. The floors plates were generally insitu reinforced ribbed

slabs with permanent hollow tile liners used as shuttering. Part of the

3rd floor slab which was a later adaption was infilled using a timber

joist floor supported on steel beams. This was a grade II listed steel framed building, 7 storey high

constructed in 1928 (see Plate-2). Its architectural form can be described

as stone classical facade. Above 5th floor, the elevation steps inwards

and extends up the 7th floor where it was crowned with a cornice. Above

this was a steep slated mansard roof with dormer windows. The structural

frame was made up of plated mild steel R.S.J's (Beams and columns) or made

up plated beams secured with rivets and either riveted or bolted end

connections. The floors plates were generally insitu reinforced ribbed

slabs with permanent hollow tile liners used as shuttering. Part of the

3rd floor slab which was a later adaption was infilled using a timber

joist floor supported on steel beams.

The internal columns were encased with 100 mm terracotta hollow

blocks, the external columns were buried within the masonry and the

internal downstand beams were concrete cased. At 1st and 2nd floors

vertical continuity of some columns was interrupted and these were

supported off substantial plated transfer beams which spanned 10 meters

and were approximately 1 meter deep. The column point loads on these beams

were approximately 1500 kN each. Transfer beams also occurred at 6th floor

to cater for the step back in the elevation. The internal columns were encased with 100 mm terracotta hollow

blocks, the external columns were buried within the masonry and the

internal downstand beams were concrete cased. At 1st and 2nd floors

vertical continuity of some columns was interrupted and these were

supported off substantial plated transfer beams which spanned 10 meters

and were approximately 1 meter deep. The column point loads on these beams

were approximately 1500 kN each. Transfer beams also occurred at 6th floor

to cater for the step back in the elevation.

The basement and lower ground floor extended out under the

Bishopsgate pavement and at the north west corner of the building the

reinforced concrete basement retaining wall bounded the perimeter of the

bomb crater. It was established from preliminary site investigations and

inspection of archival details that the entire basement had an external

asphalt membrane applied prior to casting the sub-structure concrete. The basement and lower ground floor extended out under the

Bishopsgate pavement and at the north west corner of the building the

reinforced concrete basement retaining wall bounded the perimeter of the

bomb crater. It was established from preliminary site investigations and

inspection of archival details that the entire basement had an external

asphalt membrane applied prior to casting the sub-structure concrete.

3.2 Building

B93

This property was constructed sometime between the late 1950's

and early 1960's. The building had a basement, ground and five upper

floors (see Plate-3). This property was constructed sometime between the late 1950's

and early 1960's. The building had a basement, ground and five upper

floors (see Plate-3).

|

|

Its construction consisted of a concrete cases structural steel frame

supporting hollow tiles reinforced concrete floor slabs. At 5th floor the

elevation stepped back and the perimeter cavity brickwork wall provided

support to the high level 5th floor roof.

The enclosure to the basement was a combination of reinforced

concrete retaining walls and a solid masonry party wall. The infill apron

panels were faced with slate which were faced fixed to backing brickwork

and downstand concrete beams. The parapet walls and staircase enclosures

had stone panels similarly fixed. The beam column connections consisted of

riveted seating cleats and site bolting of the beams to the cleats. Only

in some locations were the top flange restrained with a cleat. Vertical

stability was achieved through lift/staircase and flank walls. The enclosure to the basement was a combination of reinforced

concrete retaining walls and a solid masonry party wall. The infill apron

panels were faced with slate which were faced fixed to backing brickwork

and downstand concrete beams. The parapet walls and staircase enclosures

had stone panels similarly fixed. The beam column connections consisted of

riveted seating cleats and site bolting of the beams to the cleats. Only

in some locations were the top flange restrained with a cleat. Vertical

stability was achieved through lift/staircase and flank walls.

4. DAMAGE

INVESTIGATION AND TESTING

Immediately following the city bombing all efforts were

naturally directed at damage limitation measures. The general condition of

the fabric was recorded, photographed and videoed prior to it being

removed, as this may give important clues on both the blast wave pressures

and the manner in which they propagated through the structure. The

preliminary bomb damage assessment report included a program of

recommendations for further detailed inspections, opening up works and

testing required to assess fully the effects of the blast on the

structure. Immediately following the city bombing all efforts were

naturally directed at damage limitation measures. The general condition of

the fabric was recorded, photographed and videoed prior to it being

removed, as this may give important clues on both the blast wave pressures

and the manner in which they propagated through the structure. The

preliminary bomb damage assessment report included a program of

recommendations for further detailed inspections, opening up works and

testing required to assess fully the effects of the blast on the

structure.

|

Where

visual evidence of distortions, deflections, and cracking to the structure

and its finishes existed, selective local opening up of these elements

were undertaken to establish if failure have occurred.

Having identified the areas of structure for detailed

investigation, a regime of site and laboratory testing was prepared,

starting from locations of greatest visible blast damage. Analytical

methods proved very valuable here in terms of indicating areas of

possible serious overstressing of the structure. Given the

unpredictability of blast effects on buildings, it was found to be more

cost and time effective to implement methods, such as finite element

analysis that may highlight areas of damage prior to undertaking

extensive opening of the structure. Having identified the areas of structure for detailed

investigation, a regime of site and laboratory testing was prepared,

starting from locations of greatest visible blast damage. Analytical

methods proved very valuable here in terms of indicating areas of

possible serious overstressing of the structure. Given the

unpredictability of blast effects on buildings, it was found to be more

cost and time effective to implement methods, such as finite element

analysis that may highlight areas of damage prior to undertaking

extensive opening of the structure.

Static proof load testswere carried out on floor panels

which sustained maximum physical damage to compare actual

deflections with analysis predictions. These results were compared

with the results from a control area selected on the basis of least visual

damage and similarly for all other materials tested. Also, plumb line

surveys were carried out on the external elevations of both buildings,

and FE analysis results were compared with recorded lateral displacements

of the elevations of building B93. Static proof load testswere carried out on floor panels

which sustained maximum physical damage to compare actual

deflections with analysis predictions. These results were compared

with the results from a control area selected on the basis of least visual

damage and similarly for all other materials tested. Also, plumb line

surveys were carried out on the external elevations of both buildings,

and FE analysis results were compared with recorded lateral displacements

of the elevations of building B93.

5. BLAST

OVERPRESSURE EXPERIENCED BY THE TWO BUILDINGS

What needs to be estimated first, is the magnitude of the

blast pressures that the building may have experienced so that, FE

technique, for example, can be used to obtain an indication of the

dynamic response of the structure prior to it coming to rest. The

consequences of this response on the structural integrity of the building

can hence be evaluated. Royal Ordnance (a division of British Aerospace

Defence Limited) were appointed to provide information on the magnitudes

of the blast pressures experienced by the two buildings both on their

external elevations and inside each structure through gas filling. Two

distinct elements of calculations were carried out. The first, was to

perform detailed external shock reflection modelling using INBLAST. For

this analysis, 82 external test points on the elevations of building A93,

and 88 external test points on the elevations of building B93 were

selected by the author. What needs to be estimated first, is the magnitude of the

blast pressures that the building may have experienced so that, FE

technique, for example, can be used to obtain an indication of the

dynamic response of the structure prior to it coming to rest. The

consequences of this response on the structural integrity of the building

can hence be evaluated. Royal Ordnance (a division of British Aerospace

Defence Limited) were appointed to provide information on the magnitudes

of the blast pressures experienced by the two buildings both on their

external elevations and inside each structure through gas filling. Two

distinct elements of calculations were carried out. The first, was to

perform detailed external shock reflection modelling using INBLAST. For

this analysis, 82 external test points on the elevations of building A93,

and 88 external test points on the elevations of building B93 were

selected by the author.

|

|

The second element of the calculation, was the analysis of the

blast wave ingress into the structure and loads on internal slabs. This

assessment used a program named CHAMBER which assesses the internal

reflection and diffraction of blast waves entering through openings. For

this analysis, 6 internal test points on a typical floor of building A93,

and 5 internal test points on a typical floor of building B93 were

selected. The second element of the calculation, was the analysis of the

blast wave ingress into the structure and loads on internal slabs. This

assessment used a program named CHAMBER which assesses the internal

reflection and diffraction of blast waves entering through openings. For

this analysis, 6 internal test points on a typical floor of building A93,

and 5 internal test points on a typical floor of building B93 were

selected.

5.1 Building

A93

Bomb blast pressures are transient in nature and frequently of short

duration. On this building, this duration did not exceed 350 ms. The

maximum peak positive pressures ranged from 1,365 kN/m2 on the

north corner of the building (close to the bomb), to 91 kN/m2

on the south corner (away from the bomb). The arrival times of these

pressures were 12 m.sec and 138 m.sec respectively. In order to appreciate

the magnitudes of these pressures, it is worth pointing out that buildings

in the London region, including this one, are designed usually for a

maximum wind pressure of 1.5 kN/m2.

With regard to the internal pressures, their arrival times were

similar to the external pressures and their peak positive pressures ranged

from 490 kN/m2 north to 126 kN/m2 south of the

building. Careful examination of these pressures at various time intervals

concluded that these pressures subjected the floor plates to highly

complex transient behaviour in both upward and downward direction

occurring simultaneously on individual floor panels and far exceeded the

original design loads of 10 kN/m2. With regard to the internal pressures, their arrival times were

similar to the external pressures and their peak positive pressures ranged

from 490 kN/m2 north to 126 kN/m2 south of the

building. Careful examination of these pressures at various time intervals

concluded that these pressures subjected the floor plates to highly

complex transient behaviour in both upward and downward direction

occurring simultaneously on individual floor panels and far exceeded the

original design loads of 10 kN/m2. |

5.2 Building

B93

All points on the rounded corner of the building between Bishopsgate

and Wormwood Street have seen very high blast pressures that reached a

maximum value of 131 kN/m2 at first floor level. The reason

being that this corner was approximately normal to the shock waves. This

is also 87 times the wind load that the building was designed for in the

laterally. At ground floor level, however, these pressures were less than

those at 1st floor level. This can be attributed to the frictional effects

of the ground on the shock waves.

The internal pressures on the test points at ground floor level

were significantly higher than those on the corresponding test points at

1st floor level. This is attributed in this case to the large vent sizes

of the shop windows at ground floor level. The values of the internal

pressures on the ground floor ranged between 118 kN/m2 and 167

kN/m2. This can be appreciated again when compared with the

original design load on floors of 4-5 kN/m2. The internal

pressures duration was approximately 200 m.sec. The internal pressures on the test points at ground floor level

were significantly higher than those on the corresponding test points at

1st floor level. This is attributed in this case to the large vent sizes

of the shop windows at ground floor level. The values of the internal

pressures on the ground floor ranged between 118 kN/m2 and 167

kN/m2. This can be appreciated again when compared with the

original design load on floors of 4-5 kN/m2. The internal

pressures duration was approximately 200 m.sec.

It is important to note the difference in the arrival time of

the blast pressures to the two building from the time of explosion of the

bomb (15 m.sec to the external elevation of building A93, compared to 140

m.sec when it hit the external elevation of building B93; a time lag of

125 m.sec). It is important to note the difference in the arrival time of

the blast pressures to the two building from the time of explosion of the

bomb (15 m.sec to the external elevation of building A93, compared to 140

m.sec when it hit the external elevation of building B93; a time lag of

125 m.sec). |

|

6. FINITE ELEMENT

MODELLING AND ANALYSIS

6.1

General

In the analysis of the dynamic response of a building structure

to bomb blast, the following procedures must be followed [Esper &

Keane, 1995]: In the analysis of the dynamic response of a building structure

to bomb blast, the following procedures must be followed [Esper &

Keane, 1995]:

- The characteristics of the blast wave must be

determined (as explained above).

- The natural period of response of the structure (or

the structural element) must be determined.

- The positive phase duration of the blast wave is

then compared with the natural period of response of the

structure.

Based on (3) above, the response of the structure is

then defined as follows:

- If the positive phase duration of the pulse is shorter than the

natural period of vibration of the structure, the response is described

as impulsive. In this case, most of the deformation of the structure

will occur after the blast loading has diminished.

- If the positive phase duration of the pulse is longer than the

natural period of vibration of the structure, the response is defined as

quasi-static. In this case, the blast will cause the structure to deform

whilst the loading is still being applied.

- If the positive phase duration of the pulse is close to the natural

period of vibration of the structure, then the response of the structure

is referred to as being dynamic. In this case, the deformation of the

structure is a function of time and the response is determined by

solving the equation of motion of the structural

system.

|

6.2 Building

A93

The fifth floor slab of this building was modelled using ANSYS.

Two element types were used; shell element (shell 63) for the reinforced

concrete slab, and beam element (beam 4) for the steel beams. The total

number of elements in the model was 945, and the total number of nodes was

627. Each node had 6 DOF; three translations Ux, Uy, Uz, and three

rotations qx, qy, qz. The column locations were considered as support

points for the slab. Material properties of concrete and steel were

incorporated based on actual testing of the concrete cores and

examinations of the steel materials of the beams. The values used in the

analysis were as follows: The fifth floor slab of this building was modelled using ANSYS.

Two element types were used; shell element (shell 63) for the reinforced

concrete slab, and beam element (beam 4) for the steel beams. The total

number of elements in the model was 945, and the total number of nodes was

627. Each node had 6 DOF; three translations Ux, Uy, Uz, and three

rotations qx, qy, qz. The column locations were considered as support

points for the slab. Material properties of concrete and steel were

incorporated based on actual testing of the concrete cores and

examinations of the steel materials of the beams. The values used in the

analysis were as follows:

For steel:

Ex= 205 kN/mm2

n =

0.3

Dens = 7800 kg/m3

and for concrete:

Ex= 25 kN/mm2

n =

0.2

Dens = 2400 kg/m3

By carrying out a modal analysis first, using ANSYS, the natural

frequencies for the first three modes of the floor plate of building A93

were given as follows: By carrying out a modal analysis first, using ANSYS, the natural

frequencies for the first three modes of the floor plate of building A93

were given as follows:

f1= 12.495 Hz

f2=

13.459 Hz

f3= 13.490 Hz |

|

The

fundamental period of the plate was hence calculated and found to be equal

to:

T1 = 1 / f1 = 0.080 sec = 80 msec

The positive phase duration was found on the internal

pressures-time history graphs to be ranging between 20-45 m.sec. Since

this was shorter than the fundamental period of the floor plate, a 3-D

non-linear transient dynamic analysis was, then carried out in order to

determine the response of the floor slab to the internal pressures. The positive phase duration was found on the internal

pressures-time history graphs to be ranging between 20-45 m.sec. Since

this was shorter than the fundamental period of the floor plate, a 3-D

non-linear transient dynamic analysis was, then carried out in order to

determine the response of the floor slab to the internal pressures.

The blast pressures were applied on the top and bottom faces of

the concrete floor as pressure-time history graphs as produced by Royal

Ordnance. Consequently, two graphs for every node of the model were

obtained, one representing the deflections due to the pressures acting on

the bottom face of the slab, and the other representing the deflection of

the floor slab due to pressures acting on the top face of the slab. The

two graphs were superimposed over each other so that the actual net

deflection at any time can be estimated. As an example node 124 is

considered and located near the middle of the bay next to the North

stairs. It can be seen that the floor slab, at this point, was lifted

upward by 16 mm before the pressures acting at the top of the slab were

able to start pushing it downward. The blast pressures were applied on the top and bottom faces of

the concrete floor as pressure-time history graphs as produced by Royal

Ordnance. Consequently, two graphs for every node of the model were

obtained, one representing the deflections due to the pressures acting on

the bottom face of the slab, and the other representing the deflection of

the floor slab due to pressures acting on the top face of the slab. The

two graphs were superimposed over each other so that the actual net

deflection at any time can be estimated. As an example node 124 is

considered and located near the middle of the bay next to the North

stairs. It can be seen that the floor slab, at this point, was lifted

upward by 16 mm before the pressures acting at the top of the slab were

able to start pushing it downward. |

It has been demonstrated by the FE analysis that when the soffit

of the floor plate saw a positive peak pressure, it took 10 msec on

average to develop its maximum deflection which ranged between 16 mm and

24 mm. It was observed that a 5 msec time lag in the pressures hitting the

top surface of the slab was sufficient to result in a net upward

deflection of approximately 16 mm above the horizontal. This momentary

uplift of the plates will result in tension cracks to the top surface of

the structural topping. This is combined with the subsequent rebound of

the plate will cause crack aggravation over the supports, thus impairing

the performance of the bond between the concrete and its reinforcement.

This would result in failures similar to those that were recorded on

the 5th floor load test, i.e. slippage of the reinforcement over the

supports. It has been demonstrated by the FE analysis that when the soffit

of the floor plate saw a positive peak pressure, it took 10 msec on

average to develop its maximum deflection which ranged between 16 mm and

24 mm. It was observed that a 5 msec time lag in the pressures hitting the

top surface of the slab was sufficient to result in a net upward

deflection of approximately 16 mm above the horizontal. This momentary

uplift of the plates will result in tension cracks to the top surface of

the structural topping. This is combined with the subsequent rebound of

the plate will cause crack aggravation over the supports, thus impairing

the performance of the bond between the concrete and its reinforcement.

This would result in failures similar to those that were recorded on

the 5th floor load test, i.e. slippage of the reinforcement over the

supports.

Further corroboration of these pressures, is the damage observed

to the slab soffits which included cracking along the joints between the

asbestos pots, hairline cracking of the concrete between the structural

topping and the ribs. This cracking was reported in the petrographic tests

of the cores that were taken from the structural slab. Further corroboration of these pressures, is the damage observed

to the slab soffits which included cracking along the joints between the

asbestos pots, hairline cracking of the concrete between the structural

topping and the ribs. This cracking was reported in the petrographic tests

of the cores that were taken from the structural slab. |

|

6.3 Building

B93

A full 3-D FE model of this building was generated using ANSYS. Two

element types were used here too; shell element (shell 63) for the

reinforced concrete slabs, and beam element (beam 4) for the steel beams

and columns. The total number of elements in the model was 5232, and the

total number of nodes was 3912. Each node had 6 DOF; three translations

Ux, Uy, Uz, and three rotations qx, qy, qz. From Plate-3, it can be seen

that this building has a large window area in each floor all the way

around except on the west elevation (flank wall). Taking also into account

the fact that it was reported by various sources [Royal Ordnance, 1993 and

later by Mayes & Smith, 1995] that normal glass, as a brittle

material, takes only 5-8 msec to break, it was found obviously sensible

not to include the glass panels in the FE analysis. This is true as long

as the glass panels are weak enough not to transfer any load to the

structural elements (such as frame members).

Material properties of concrete and steel were incorporated

based on actual testing of the concrete cores and examinations of the

steel materials of the beams. The values used in the analysis were as

follows: Material properties of concrete and steel were incorporated

based on actual testing of the concrete cores and examinations of the

steel materials of the beams. The values used in the analysis were as

follows:

| For steel: |

For concrete: |

Ex = 205

kN/mm2

n = 0.3

Dens = 7800 kg/m3

|

Ex= 24

kN/mm2

n = 0.2

Dens = 2400 kg/m3

| |

By carrying out a modal analysis first, using

ANSYS, the natural frequencies for the building were given as follows:

f1= 1.899 Hz

f2=

1.961 Hz

f3= 2.586 Hz

The fundamental period of the plate was hence

calculated and found to be equal to:

T1 = 1 / f1 = 0.527 sec = 527 msec

The positive phase duration was found on the internal

pressures-time history graphs to be ranging between 50-80 m.sec. Since

this was shorter than the fundamental period of the floor plate, the

response of the building was impulsive, and the proper analysis that would

be used is a non-linear transient dynamic one. Since the main concern was

concentrated on the actual stability of the building, a quasi-static

analysis was carried out as follows: The blast pressures were applied at

different time intervals as a static load that has a variable value

throughout all the elements forming the facades of the building. These

values were extracted from the pressure-time history graphs produced by

Royal Ordnance at each specific time interval considered in the analysis.

This has allowed one to look at the maximum deflection that could have

been experienced by the building with considerable saving of computer time

and analysis efforts (such as feeding all the pressure-time history graphs

to all the locations of the selected external 80 test points on all the

elevations of the building). The positive phase duration was found on the internal

pressures-time history graphs to be ranging between 50-80 m.sec. Since

this was shorter than the fundamental period of the floor plate, the

response of the building was impulsive, and the proper analysis that would

be used is a non-linear transient dynamic one. Since the main concern was

concentrated on the actual stability of the building, a quasi-static

analysis was carried out as follows: The blast pressures were applied at

different time intervals as a static load that has a variable value

throughout all the elements forming the facades of the building. These

values were extracted from the pressure-time history graphs produced by

Royal Ordnance at each specific time interval considered in the analysis.

This has allowed one to look at the maximum deflection that could have

been experienced by the building with considerable saving of computer time

and analysis efforts (such as feeding all the pressure-time history graphs

to all the locations of the selected external 80 test points on all the

elevations of the building). |

|

7. CORRELATION BETWEEN

DAMAGE AND FEA RESULTS

Tremendous damage was observed in the Bishopsgate incident. In

buildings close to the explosion, floor slabs were momentarily lifted,

load bearing walls moved and became out of plumb, and hidden damage

resulted. Hidden damage in building structures due to dynamic loading

became of more concern to engineers particularly after the investigation

of damaged buildings following the Northridge earthquake [NCE, 1994] and

the Kobe earthquake [Esper & Tachibana, 1995] where the same types of

damage described above were found. Tremendous damage was observed in the Bishopsgate incident. In

buildings close to the explosion, floor slabs were momentarily lifted,

load bearing walls moved and became out of plumb, and hidden damage

resulted. Hidden damage in building structures due to dynamic loading

became of more concern to engineers particularly after the investigation

of damaged buildings following the Northridge earthquake [NCE, 1994] and

the Kobe earthquake [Esper & Tachibana, 1995] where the same types of

damage described above were found.

In the case of this explosion, building A93 exhibited damage in

the form of cracking, high speed spalling and scabbing of concrete cover,

shear and/or tensile failure of columns, upward failure of floors,

snapping of rods and prying of frame connections. The main feature of this

damage was the cracking in the concrete floors and failure under load

testing. This was predicted also in the FE analysis. Location of cracking

zones were highlighted in the FE analysis and these fine cracks were found

as predicted by the FEA when the preliminary inspection / investigation

did not report them. This was particularly important when these cracks

were discovered in the mezzanine floor (2nd floor) where timber joists

exhibited longitudinal fine cracks that were difficult to observe in the

preliminary investigation. In the case of this explosion, building A93 exhibited damage in

the form of cracking, high speed spalling and scabbing of concrete cover,

shear and/or tensile failure of columns, upward failure of floors,

snapping of rods and prying of frame connections. The main feature of this

damage was the cracking in the concrete floors and failure under load

testing. This was predicted also in the FE analysis. Location of cracking

zones were highlighted in the FE analysis and these fine cracks were found

as predicted by the FEA when the preliminary inspection / investigation

did not report them. This was particularly important when these cracks

were discovered in the mezzanine floor (2nd floor) where timber joists

exhibited longitudinal fine cracks that were difficult to observe in the

preliminary investigation.

|

In the case of Building B93, less damage was observed to the

floor slabs because it was located much further than building A93 relative

to the bomb. However, what was of a major concern in this building is the

effect of the blast on the stability of the building and its residual

strength to carry the original design load. This urged the need to look at

the global behaviour of the structure and the magnitudes of permanent

deflections in all three direction that may have resulted in the

structure. Plumb survey was carried on the structure, along with all the

other specified regular tests. Finite Element results from the 3-D

quasi-static analysis over different time steps of the load showed good

correlation with both the deformed shape and displacement magnitudes of

the structure at corresponding points. Maximum deflection of 25 mm that

was observed in the plumb survey on line V7, for instance, had a

displacement value in the same direction of 22 mm in the FE analysis.

Although these magnitudes may not seem particularly significant, design

check calculations were carried out in order to predict the additional

forces and moments values induced, in the structural frame, by the new

displacements, and the adequacy of the frame to carry these forces and

moments. Additional bracing was needed in this case for the structure to

carry on functioning in the manner it was originally designed for. In the case of Building B93, less damage was observed to the

floor slabs because it was located much further than building A93 relative

to the bomb. However, what was of a major concern in this building is the

effect of the blast on the stability of the building and its residual

strength to carry the original design load. This urged the need to look at

the global behaviour of the structure and the magnitudes of permanent

deflections in all three direction that may have resulted in the

structure. Plumb survey was carried on the structure, along with all the

other specified regular tests. Finite Element results from the 3-D

quasi-static analysis over different time steps of the load showed good

correlation with both the deformed shape and displacement magnitudes of

the structure at corresponding points. Maximum deflection of 25 mm that

was observed in the plumb survey on line V7, for instance, had a

displacement value in the same direction of 22 mm in the FE analysis.

Although these magnitudes may not seem particularly significant, design

check calculations were carried out in order to predict the additional

forces and moments values induced, in the structural frame, by the new

displacements, and the adequacy of the frame to carry these forces and

moments. Additional bracing was needed in this case for the structure to

carry on functioning in the manner it was originally designed for.

|

|

8. CONCLUSIONS

Given the unpredictability of blast effects on buildings, it was found

to be more cost and time effective to implement methods, such as finite

element analysis that may highlight areas of damage prior to

undertaking extensive opening of the structure.

This was the case in both building A93 and building B93. In the

former, the scope of testing was greatly reduced in terms of opening up of

beam-column connections and directed the next investigation / testing

stage in a manner that was more efficient and economic. Decisions made

later regarding future use of different parts of the structure (e.g. floor

slabs, steel frame, etc.) carried great confidence particularly that they

were backed up by site testing results. This was the case in both building A93 and building B93. In the

former, the scope of testing was greatly reduced in terms of opening up of

beam-column connections and directed the next investigation / testing

stage in a manner that was more efficient and economic. Decisions made

later regarding future use of different parts of the structure (e.g. floor

slabs, steel frame, etc.) carried great confidence particularly that they

were backed up by site testing results.

Although the response of building B93 was transient, but

considering the type of concern encountered here (i.e. stability of the

structure and the magnitudes of the displacements associated with it), it

proved to be very cost effective to carry out a quasi-static analysis

particularly when taking into account the size of the structure modelled

here, and the efforts involved in terms of feeding all the necessary

information to carry a non-linear transient dynamic analysis. The other

advantage is obviously the saving in computer time necessary to carry out

the non-linear transient analysis. Once more, and being more important

here, the combined analysis and testing carried out hand in hand proved to

be very efficient in reducing the scope of carrying either of them

separately, and having at the same time more confidence in the results, in

addition to achieving the best economic solution. Although the response of building B93 was transient, but

considering the type of concern encountered here (i.e. stability of the

structure and the magnitudes of the displacements associated with it), it

proved to be very cost effective to carry out a quasi-static analysis

particularly when taking into account the size of the structure modelled

here, and the efforts involved in terms of feeding all the necessary

information to carry a non-linear transient dynamic analysis. The other

advantage is obviously the saving in computer time necessary to carry out

the non-linear transient analysis. Once more, and being more important

here, the combined analysis and testing carried out hand in hand proved to

be very efficient in reducing the scope of carrying either of them

separately, and having at the same time more confidence in the results, in

addition to achieving the best economic solution. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author gratefully acknowledges the valuable contribution

made by William Keane of Griffiths Cleator & Associates. The author

also wishes to express his appreciation for the support provided by

Griffiths Cleator and Associates, University of Westminster, and Taylor

Woodrow Construction Holdings Limited. Finally, the support provided by

the help desk and other members of the STRUCOM company on ANSYS is greatly

appreciated. The author gratefully acknowledges the valuable contribution

made by William Keane of Griffiths Cleator & Associates. The author

also wishes to express his appreciation for the support provided by

Griffiths Cleator and Associates, University of Westminster, and Taylor

Woodrow Construction Holdings Limited. Finally, the support provided by

the help desk and other members of the STRUCOM company on ANSYS is greatly

appreciated.

REFERENCES

Esper, P., and Keane, W., The St Mary Axe /

Bishopsgate Experiences on the Dynamic Response of Buildings to Bomb

Blast, A paper presented and discussed at the Institution of

Structural Engineers, Thames Valley Branch, on Wednesday 4th October 1995

at 6 p.m., London, UK.

Esper, P., and Tachibana, E.,

The lesson of Kobe Earthquake, Geohazards and Engineering Geology

Conference, Coventry, 1995.

Mayes, G. C., and P. D. Smith,

Blast Effects on Buildings, London, 1995.

New Civil Engineer (NCE), 29th

September 1994 edition, London, UK.

Royal Ordnance, Report on the

Analysis of the Effects of the Bishopsgate Bombing on Hasilwood House,

Swindon, 1993. |

|